The Cure For Sleep is a memoir about effort. How we choose to change in response to unsought gifts, sudden emergencies and strangely-timed encounters.

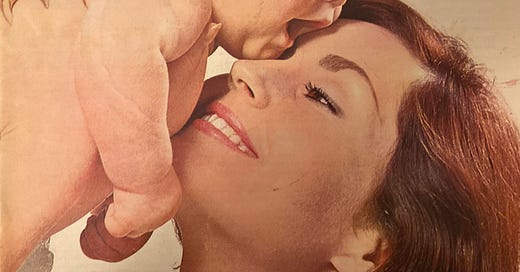

The May extract concerns how I attempted to bond with my small son after a sudden near-death experience which left with me none of the tender feelings of new motherhood as described in books, baby manuals and forums.

After reading, do share a short true tale of your own - no more than 300 words – on the theme of bonding through effort rather than instinct - with a person, family, community, place or creature – in the comments section.

You can read the stories already contributed by readers over on The Cure For Sleep website

may’s extract

Our survival kit would be composed of no received ideas, only food, shelter, cleanliness, and warmth (of skin, voice, gaze). I would learn him, and he me.

I was still terrified of being left all alone with a baby, but now I felt determined, and yes, a little excited too. Because hadn’t I done this before, as a child? Sent half of me ahead up the lane, while my other part trekked slow to safety? And mad as it would sound to anyone if they knew, how did it matter what moved me so long as it was felt by my child as love?

I emptied the little nursery of childcare manuals and baby magazines, and restocked it with true stories of endurance, endeavour: books I’d bought compulsively over the years, but never bothered to read, as if just having them to hand would make me braver, by contagious magic. Scott’s diaries. Thoreau’s. Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass: that epic celebration of the body, free love and free-thinking – a set text from long ago that I’d only skim read then, finding it too alarmingly-far from my own cramped sense of self.

Made then a base camp out of blankets and pillows at floor level where I could manage best with my bad back. Carried up a flask, our camping radio, candles, cartons of formula, nappies, changes of clothes, and food rations for me.

Went back down, panting with effort and adrenaline, and asked Nye for the baby. I need to be alone with him now until I go through my fear and out the other side…

Then, over my shoulder as I went up, a grim little joke to show I was not mad or manic. Only attempting heroic stoicism, in the style of Titus Oates. I’m just going upstairs, I may be some time.

Most new parents prefer their child asleep. In repose, eyes closed and quiet, a baby is a sweet good thing, easy to love.

But now, I needed my son awake. On the floor in the far corner of his nursery, with a draught from the window coming in, I stripped him, then me. Nappy, maternity pants, nursing bra; each tiny movement of his limbs and mine making pain flare where I’d been sliced and stitched twice-over. Next, using nail scissors I couldn’t imagine taking ever to his unpredictable fingers, I cut us free of the plastic name shackles put on at the hospital (left on so long through my fear of rupturing again).

And there we were at last: two naked animals, wide-eyed and facing one another.

I put my lips to the soft place on top of his head where smell pulsed strongest. Nosed at him, but still nothing moved in me. Birth cries, hot skin; the metallic tang which triggers recognition: all this was missing between us, even before the still more violent separation that came later with the haemorrhage. Delivered by emergency Caesarian after a two-day labour, he’d arrived still and silent, and was taken away from me out of view. When placed in my arms long minutes later, he was already blanket-wrapped and wiped clean of his messy, necessary scent.

He struggled now against my chest that was not his father’s, and began to fuss.

Panic, self-disgust. I was not what he wanted.

I laid him away against my bent knees still better to see each other and began to sing. It was only, at first, for myself; a whistling in the dark, for courage; a way to ease my unease. But his body began to respond, tensing and turning about in search of the sound, so that I tuned myself to him in turn, making with my face each shape that passed across his, my song modulating as I did. If his hands spasmed closer to mine, I brought them to my lips and kissed them, still singing so he’d feel the hum of me against his skin. When he made a noise, I echoed it. In this way, through a sort of whale music, we floated free from clock-time, our culture. Began, unobserved, on the depth work of becoming mother and son.

So moved by this Tanya, thank you for sharing it. I think one of my most intense and valuable bonding experiences has been with Northumberland. I’ve tried to explain a little more about it here:

My tale is one of connection with land, with sand and soil. It is a tale of immersion in water that burns me, in salt and seaweed. And it is a tale of inhaling the sky and breathing out fear.

For years I struggled with a strong sense of claustrophobia that I was somehow experiencing in the middle of nowhere. I missed the soot in my nostrils and grease on my face from packed tube trains. There was an anonymity in the city that could be lonely, but somehow I fitted in, wore the grime as a second skin. But moving into the wilderness, naively expecting the good life, was a different kind of isolation. There were visceral reminders that I was still alive: puckered lips around my breast, tiny nails jabbing my ribs under the duvet and gritty eyes staring with an exhaustion that has perhaps never really shifted. My sense of self was all wrapped up in many babies, and the rest of it was lost to a man who no longer lies next to me.

I would walk the Northumbrian beaches with the youngest strapped closely to my chest, a small girl in each hand and the oldest running ahead on legs that effortlessly pounded the waves as they rolled towards us. We were a tribe. Whilst the children might have felt an innocent freedom on that sand, I was bending down and clutching pieces of sea glass like talismans, desperately trying to find myself amongst the bladderwrack. I began to fill jars with smoky blue shards, rubbed smooth by the tides, translucent milk drops and bottle green nuggets that glowed in my kitchen.

After a long time, I could no longer smell the city on my body. My lips were being kissed only by sea spray, but I could lick them and recall myself in an instant. I started to lean in to the rhythm of the waves, listen to the curlew’s call hanging on the breeze, enjoy the sharp shells under my toes. I have exhaled this air so often, cried so many tears that the sand is soaked, my own salt mingling with the sea. Now I am not sure where the wilderness ends and I begin.

I'm a bit late in responding here, but I love this extract, and how trepidatious it made me feel while reading it. Because of how measured your steps were in preparing for this meeting of mother and son, your own fear etc comes through. What do you do when it doesn't happen like all the books and magazines and experts say? You go back to the very Beginning...stripped bare, no one else to interfere, echoing Wordsworth: "THIS is the forest primeval..." My own tale on bonding includes sound as well, in the sharing of music. I should note that while I was writing this brief sketch my curiosity propelled me to Google. Arthur, the gentleman mentioned here, passed away in 2013 at the age of 77. I discovered his all too brief obituary online. But I also discovered a photo of him on the website of the agency he received support services from, and in the photo, he is smiling--one arm held close to his body, the fingers of his other hand having just made sound from a guitar laid held across his lap by a staff person. Maybe I was the first to try and develop a true connection with him, but it's good to know that I was not the last and perhaps had a hand in changing in his life for the better.

****

ARTHUR

He sat alone, one arm across his body while the fingers of his other hand tapped a rhythm on the hand held flush to his chest. He often strained to one side of the chair, pulling at the chest and groin restraints, legs stretched out and ridged, punctuated with a guttural yell of displeasure? pain? He wore a sweatshirt and sweatpants stained from lunch, and white tube socks. He mashed and gummed his tongue: tardive dyskinesia, a side effect of antipsychotics I’d later learn. I didn’t question his aloneness or the restraints because I was too young and new to the work. It took a year and various personnel changes before I attempted my own relationship with Arthur.

Each night I wheeled him into the dining room and I sat at the table writing my end of shift notes. As I wrote, I talked to him: It’s my turn to make dinner tomorrow night for everyone, Arthur. What should I make? Would you like to help me? I did this for months, writing and chatting to him and occasionally spooning him butterscotch pudding with his evening medications. Then I started playing music I brought from home—new age piano, Enya, Beatles, classical—even though it wasn’t clear how much he could hear. The right side of his face was perpetually red and his ear deformed, the cartilage mottled and bumpy, cauliflower ear it’s called—a result of him slapping the side of his face and ear.

One night I pressed play for an Irish/Norwegian duo called A Secret Garden, violin and piano. Arthur stopped tapping his fingers, slowly leaned his body closer to the stereo. I wrote and watched him. When I finished writing and began to move away he grabbed my hand. He brought it to his red and mottled ear, and he tilted his head resting it on my hand. We stayed like that for minutes, music filling the space around us. He could hear enough to appreciate music, or at least feel it. And we had made a connection.