your invitation to write

When writing The Cure for Sleep, perhaps my favourite parts to work on were those where I got to celebrate my own and others’ skill: how my mother, as a young woman before I was born, defied her parents’ low hopes for her future to become (after thousands of hours of difficult training) a skilled shorthand-typist in the local bank; how my gentle husband taught himself to cultivate plants from seed as a way to cope with our otherwise barren-feeling time of infertility; how, at 42, I embarked - after years of private diaries - on the public, poolside mile of writing that would change my life. All these and more.

Yes, it was delicious to spend time describing and celebrating effort and its reward in a cultural moment that so often pays attention to more superficial forms of success. I hope you will likewise enjoy writing about this for our shared project here.

So: Tell me about a skill you possess. I want you - in the way of Whitman - to ‘sing the song of yourself’. Celebrate something you are able to do that gives you quiet pride - or even exaltation. OR: Describe a skill you admire in someone else.

[Please read the guidelines for contributors if this is your first submission to the project.]

A suggestion for more work around this theme in your private creative practice: Make a list of everything - large or small - you can do with ease, pleasure and skill. How many of these things are still a regular part of your week? And can you find more ways to share them with others?

You can read the stories already contributed by readers over on The Cure For Sleep website.

the cure for sleep: extract

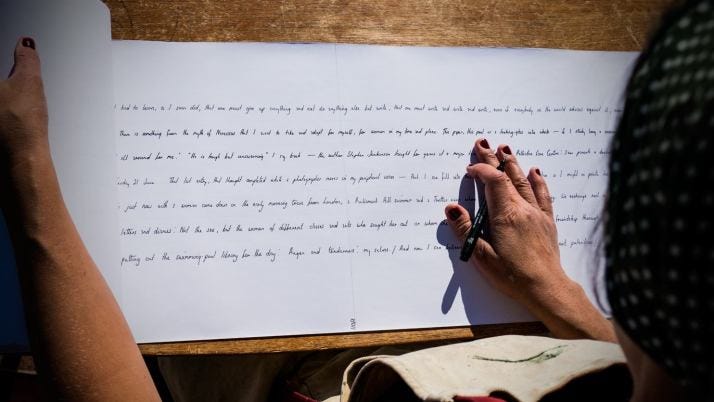

To write a mile, I’d need to do thirty-five of what I’d call my laps of longhand. Too many horizontal lines to fit on a single scroll, so long yet so narrow. And so I’d use five rolls: one for each of the blue-edged swimming lanes, and with seven lengths of writing on every one. With the small and neat way I formed my letters, I calculated that I’d need to do a hundred thousand words: a novel-sized undertaking, all done by pen on paper in full view of swimmers.

I conducted all this odd planning with as much, or more, focus than I’d ever expended on paid work, conscientious though I’d always been. It came from a part of me never used before, operating without reference to anything except my own curiosity and will to make something that satisfied my sense of beauty. As birds are when working at their nests: nearest I can find to describe it.

/…/

And of course the first day was awkward, and awful.

And the next. And the third when it rained, and I was the only person there, working under the bike shelter while wind blew my books off their stepladder library. It was as if I’d fitted out a fancy new shop at great cost for the notice of no one…

But I kept going back, whatever the weather, affecting not to mind the unreadable looks of those who only watched from a distance. Like the mirror I placed on the floor as a child, trying to make contact with God and my father. All the hours lying in fields pretending sleep and hoping to be found. As I held out grass to cows on the far side of the field from the bungalow. My long nights of learning quotes by heart for a few undergraduate exams. Resolving to turn early motherhood into an expedition. All these earlier exercises in persistence – even the hopeless ones, especially those – kept me knelt there, under the tree.

Then one morning the sculptor came to visit. Sitting on the grass across from me, he asked a few questions then understood everything. My reason for kneeling (a posture that recalled both prayer and the pillory: the stakes to which women are so often tied – purity, disgrace). The power of my being headscarved at work on a long piece of paper that was in the lineage of tapestries made by so many anonymous women going back through time. Yes, yes. And the scale of it, the absurd patience required. Yes.

Telling me then, before he went back to his own art, not to judge my success by how many people drew close. It was a tempting measure, but not the most important. It would be worth all my risk and effort, this huge and true display of . . . vulnerability, if it brought just one decisive person into my life (as my essay on the railings had connected him and me). He told me then how – as a still emerging artist in the seventies – he’d had a solo show in an obscure alternative London gallery. Nothing very likely to change his fortunes. But on a day of heavy rain, a curator from an American museum stumbled in on it by chance and a few years later included him in a show at the Guggenheim that lifted him to international prominence thereafter.

Once he was gone again, the paper no longer seemed so silly or resistant. I forgot my audience, or lack of it, and went down deep into my own stories, discovering there a powerful new dimension to what I was doing.

How had I not seen it till now? My mother’s days had come alive for a while by marks made on paper: that rapid shorthand which caught every word from the mouth of her male boss. And through her rare skill, she gained entry for a while to the worlds of regional banking and local politics – little ponds, perhaps, but she felt herself a big fish at swim in them: all that was best in her being fully used and recognised. And now there I was, a half-century later, also using pen and paper to break open a larger life. What a heady, hardy feeling: to be reclaiming the stories of my female line and laying them out like brickwork – word by word, inch by inch. Building foundations for a legacy that just might last.

Shadrick, Tanya. The Cure for Sleep (pp. 186-189). Orion. Kindle Edition.

this month’s extras

You can listen (again) to my conversation with US author Dr Skye Cleary which we shared to celebrate the UK launch of her fascinating new book: How To Be You - Simone de Beauvoir and the Art of Authentic Living. I asked Skye what de Beauvoir meant by authenticity, and why this still offers us radical possibilities for how to live now

Quote on my chalkboard kitchen wall by Neem Karoli Baba: Love people and feed them.

I will squeeze lemons and peel ginger and add water and cinnamon and honey and then simmer, pour, deliver.

I will pick chicken from bone, add broth and vegetables, season and serve soup when you feel depleted.

I will make fresh scones and clotted cream and homemade raspberry jam and tea when you come home from England wishing you were still there, young and full of dreams of travel.

I will shave dark chocolate into full fat milk with sugar and just a touch of cayenne and cinnamon to warm February bones.

I will send cookies and brownies to your air force base and when you are home on leave I will fill the kitchen with every favorite, every dinner a Sunday meal and eggs every which way for breakfast.

I will step away and let yeast and water and salt and flour become better than the sum of their parts and bake in a blazing cast iron pot and call you to the kitchen while the bread is still warm.

I will let flour fly and sugar sparkle, berries will join hands, buttery crust will flake and pie will be served.

I will grind the beans and pour the water into the French press and pick a mug I think you will like.

I will pick and cook and peel and process beets in a kitchen stuffed full of hair frizzing humidity.

I will stir, mix, blend, chop and toss, simmer and grill, boil and broil, bake, saute and simmer, coat in olive oil and season with salt and roast for you.

I will feed you like an oak feeds squirrel and jay, like goldenrod feeds September bees, like snowmelt feeds streams and rain feeds puddles. I will feed you like a middle-aged lady feeds her birds.

“Tell me about a skill you possess”. My heart sinks heavy and I want to hide. Please don’t ask me this. I don’t have any skills. Not now, age 50. Not anything that would mark me out as special, different, unique, worthy of the telling. My first instinct: to tell you about the skills of others. My friends, my family, the little boy who lives next door and pretends to be a dragon. Or to say that I did, once, have skills, but so distant in time it’s barely memory. Talents and abilities I possessed as a little girl. I could do backflips! Turn endless perfectly dizzying cartwheels until I collapsed in a giggling heap, the world still spinning around me.

And yet. My friends, my colleagues – have they not sung the song of myself to me, when I could not (or would not) sing the song myself? My friend who admired my hand-knit jumper, striped in the colours of the summer Hebridean sea, unknowing of the hidden months-long labour of its creation. A colleague who felt able to share with me some of her deepest worries, knowing she would be truly heard and seen by me in the telling. Awards given more than once for being ‘best educational supervisor of the year’ from former students.

Perhaps what I have lost is not the actual skills, but rather the skills of seeing, of recognising, of valuing. My skills. Myself. Perhaps it’s now more than time to regain this long-lost skill.