“I love this book. Tanya’s story is moving and inspiring. Her thoughts and writing are well considered, courageous and true: real art. Just reading her is pleasure”

Amy Liptrot, author of The Outrun

This month’s extract from The Cure For Sleep is about time. In the few years when I worked as a hospice scribe, I was privileged to share time with those who had very little left - exchanges that deepened still further my determination to be changed forever by my own sudden near-death.

After reading, do share a short true tale of your own - no more than 300 words – on this theme in the comments section. When has time taken on strange new dimensions for you?

You can read the stories already contributed by readers over on The Cure For Sleep website

september’s extract

ALL THINGS BRIGHT AND BEAUTIFUL in my second life came from those darkest hours in the car park, when I chose time as my teacher, and decided to apprentice myself to it.

This element in which we are all of us at swim or adrift – natural resource that can’t be dammed for future use, or gathered back in (both of which I’d always tried to do, even as it ran through my fingers). And it occurred to me then that there was one place where my small, spare ration would have true use and value: among those who had very little left. People who were coming close to their end: they may have a thirst to speak frankly, and by listening I might meet my own need for a deeper communion than could be got in day-to-day talk with colleagues and friends.

Once my daughter was settled in nursery, I drove out beyond the bounds of town to the region’s hospice to explain and offer myself: They had a befriending programme where volunteers were trained to give an hour of respite to those caring for terminally ill family members, but might they consider me for a role of my own creation? To let me be alongside any patients pained by regret, as I had been? An encounter different in kind to the slow and steady talking cure of counselling; a discomfort not touched by opiates from the palliative care team; what perhaps the chaplains there did for those who were still comfortable with people of faith? Me as a lay version of that? A person able to simply sit and listen to difficult things that could not be fixed. There to help the dying preserve in words moments of joy that were strong in mind as they got ready to go?

‘Trimming and folding paper, thirty years. Machines do it now, but that was my work.’ The man across from me mimed the robotic movements he’d performed for so many decades, then shook his head. Disbelief, amusement, disgust? I couldn’t tell.

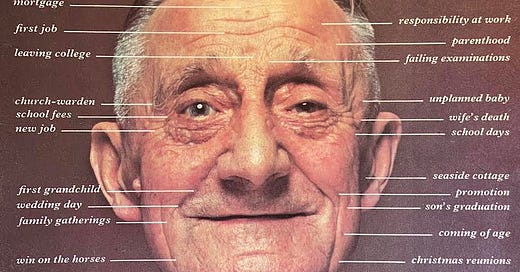

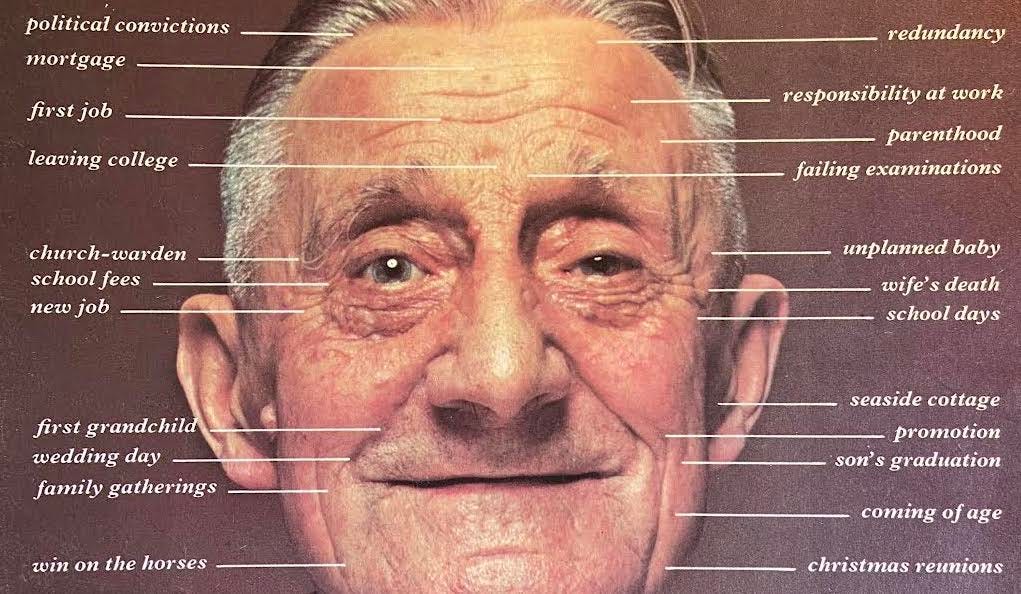

It was a Sunday afternoon in a quiet cul-de-sac of a post-war suburb, and he was my first hospice client. In the next few years I would become adept at this: working with the Möbius-strip sensation felt whenever a dying person confided a thing that twisted time and conversation into a strange new shape. I even became bold enough to invite it, saying – just minutes into first meetings – what was true: That we may only have here and now together, and so they should speak to me about whatever was most urgent. There was no time for small talk. Instead: What stories did they not want lost with their life’s ending?

But I was new to it then, and clumsy. A silence happened.

I looked at his photos spread across the polished mahogany table. There were pictures of the home itself being built, and I saw the beautiful achievement of it for a boy born poor during wartime, whose education ended with evacuation.

‘What did you spend your pay packet on, once the bills were paid?’

Idiot. The kind of question an oral historian asks, not one soul to another when death is near. But it animated him at last, this family man of few words who was being prompted by his loving wife, so we’d made more of a list than a life story: his James 125 motorbike, their green Morris Austin, dancing at the Streatham Locarno.

Now, like a music box wound and opened, he spoke for long, lyrical minutes of a single night beside an Italian lake in the late 1960s: their first foreign holiday, camping. A storm blew up after dark so that the canvas strained and the children cried. He went out into the wind and rain with the mallet to secure the pegs and guy ropes, and found himself in the company of every other man on the site – all of them working together after that to fasten everything that threatened to blow loose and damage the tents, their families.

He died before I got the notes typed up; his wife thanked me for them, and said his anxiety dropped away soon after our recording.

It was such a slight and uncertain service I had set out to render, but neither was it nothing, I told myself whenever a new address and name came through.

You know those big clocks they have in institutions - schools, hospitals? You know how they go when the batteries are almost dead? The second hand keeps flicking forward and dropping back. It counts the seconds, but the hands don't turn. It can fool you - you look up and think "Oh, it's 9.30" or ten past two, or whatever, and then when you look back half an hour later it's still 9.30, or ten past two, or whatever.

Time in waiting rooms is like that. It ticks by, but somehow it doesn't move. It becomes liquid - pooling, eddying, slipping between your fingers.

Waiting rooms are liminal spaces. You sit there, suspended between health and sickness, barrenness and pregnancy, hope and fear. Everything is different. Footsteps resonate. Conversations happen in lurching whispers. Your heartbeat might be the fiercest thing in the universe. You hold your most private fears in your lap in a relentlessly public space. Out there in the real world you have multiple roles. in here you only have one.

The last consultant I had used to have ridiculously overbooked clinics. It must have been hard for him: there's a limit to how quickly you can see a patient, listen to them, examine them, and then work out a plan with them. Once you got in there you were never rushed, he gave you all the time you needed. You just had to wait for it.

We expected to wait a couple of hours. We took books and people-watched. We kept our conversation light and meaningless. What is there to say, anyway? I love you. I'm scared. How long have we got in the carpark? Do we need to get milk on the way home? I love you. I'm scared.

So, so very late to the game...mind and body are just having a rough bit of it so stringing words and together is possible for only the briefest of moments. Still a work in progress this piece, but as always, your words Tanya beget others.

****************************

August 2021

mess

clutter

dust

hearts on wall

in a frame and

hanging from strings

raindrops like lace on screen

fern under glass

cat sniffs air

eyelids close

eyelids open

light pierces left eye

shoulders sink

so..heavy.

h e a v y.

h e a v y.

single words

fragments

half thoughts and no end

in this room

with shades down

beneath blanket

breathing—

in

out.

nine years so far

of breathing

and watching

others move on:

chronic illness is

hard time