The Cure for Sleep: Reading

Season 2, 008: Scenes from our reading lives: What books (given, lent, lost, found, shared, annotated, more) - or memories of reading/being read to - are at the heart of our own stories?

The Cure for Sleep was published in January 2022, and ten months later my last public events for it have only just finished. And so this book that contains much of my and my husband’s shared life this last thirty years? It can rest now on a shelf at home, just one among many hundreds, which is as it should be. And Nye and I can begin to return to what we were before publication day: readers of books, rather than characters within one.

And if you’ve read our story, you’ll know how much our life has been shaped by the words of dead and distant authors, our main companions through our shy twenties. As two introverted working-class kids who had the good fortune to meet and band together at university, we used our evenings and weekends to read, read, read:

Going magpie-like through biographies became our shared passion: how Lawrence made a home with Frieda from each rented cottage by distempering the walls, sewing lampshades; the way Woolf and the rest of the Bloomsbury Group remade arrangements for living and loving; what it cost women poets of my mother’s generation when they dared to voice their sexual selves.

We were learning through those late nights of our early twenties (so we believed) to go beyond our class, its constraints, and design a life of our own

Shadrick, Tanya. The Cure for Sleep (p. 74). Orion.

Later, when my perspective of life had been shaken to its core by my sudden near-death as a new mother, I found in Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass a book like a secular prayer to keep close for courage as I tried to design a new way of being that could honour even a little of the great generosity and connection-beyond-work-and-family I’d experienced in what I believed were my last minutes of living. And lines from that book run now through my own as section epigraphs: a small way of honouring my debt to it.

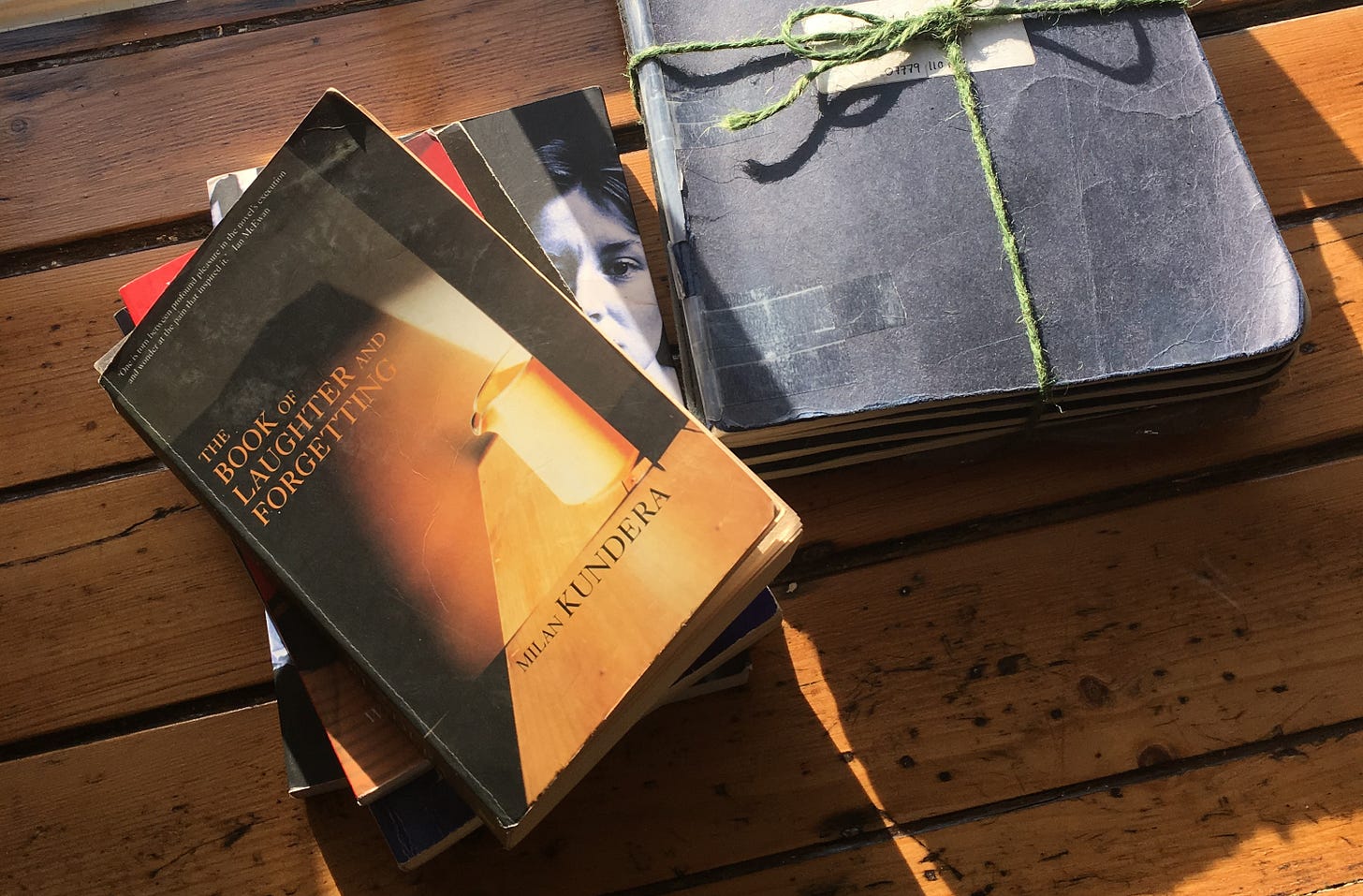

On Laughter and Forgetting

A book story not in The Cure for Sleep, but key to its being written, relates to a copy of The Book of Laughter and Forgetting by Milan Kundera that had been left by a previous guest in a hotel room on my childhood coast. It was June 2018, in the early aftermath of a great loss. I took Kundera’s novel out onto the cliff path with me, even though I was finding it difficult to read with pleasure or concentration for the first time: all books become a painful reminder that I had never written one, and likely never would now I was so mired in emotional mess.

But the minute I opened it something uncanny happened.

There on the page was an unusual word of great significance in my relationship just ended. And immediately after this, a ray of light fell across the paper, so bright I had to close my eyes. And as I did, a thought came - unbidden, from outside; as if said to me by another person, although I was quite alone.

You will write a book. Soon. And it will have a title like this one. Simple words, big forces. It will be the story of your small personal life - the only story you have - and yet done with the purpose of calling forth the stories of others.

The light shifted. I went back to Kundera. Read him in a single sitting as I hadn’t managed with a book for several years. But it wasn’t an instant and completely healing epiphany. Much of my life continued to feel only failed, mistaken, for many months to come.

But at the very end of the following summer? The idea for The Cure for Sleep arrived with me, all at once, and by a similarly uncanny method: just as predicted in that strangely-lit clifftop moment.

your invitation to write

One of the deepest pleasures while doing festivals, workshops and mentoring sessions this year was to learn in return what books or reading habits had life-shaping importance to others. Hence this month’s prompt, below…

Share a scene or story from your intimate life as a reader: your relationship to an author, a book, a character, or only passages/lines from a story or poem. Or: tell us about an experience of reading, the act of it - alone or with others - that has made a mark on you.

[Please read the guidelines for contributors if this is your first submission to the project.]

You can read the stories already contributed by readers over on The Cure For Sleep website.

further reading

from ‘Atlas of the Difficult World: XIII’ by Adrienne Rich

I know you are reading this poem as you pace beside the stove

warming milk, a crying child on your shoulder, a book in your

hand

because life is short and you too are thirsty.

I know you are reading this poem which is not in your language

guessing at some words while others keep you reading

and I want to know which words they are.

I know you are reading this poem listening for something, torn

between bitterness and hope

turning back once again to the task you cannot refuse.

I know you are reading this poem because there is nothing else

left to read

there where you have landed, stripped as you are.Read the whole poem here, or find it in An Atlas of the Difficult World: Poems 1988-1991 (W.W.Norton)

In 2003, my partner and I arrived in the high, thin air of Mexico City at the start of a year long adventure. The culture shock was massive, a combination of altitude, the bustle of 10 million people, unfamiliar food, smells, faces and so much noise. The hostel overlooked the Zocalo, with its Spanish colonial buildings sitting on top of an aztec temple, the main square of the city. I felt homesick, shocked and disoriented and searched for the familiar. We travelled lightly and the hostel had a shelf full of books left by travellers coming and going from all parts of Central America. I found a battered copy of McCarthy’s Bar by Pete McCarthy, a story of his travels around Southern Ireland. I took it with me when we hopped on the bus south to the Mayan riviera and read it cover to cover on the 20 hour journey imagining the green fields of west cork as we drive along the parched Mexican highways scattered with cacti and dust. Arriving in Playa del Carmen in Yucatan with its turquoise sea and blazing white beaches and another hostel, I swapped my book for another battered novel and lay reading in a hammock. That carried me on to a jungle traveller village in Guatemala with an open air jungle canopy bathroom and howler monkeys in the trees as I sat reading on the loo. And so it went. I read, I passed my book on, I swapped and shared battered books with global travellers all the way through Belize, through LA and onward to Fiji, on campsites and hostels across New Zealand and Australia. The comfort blanket of novels and autobiographies and books I never dreamed I would read. Adventure, poetry, classics. Anything that was there- I was open to it all. I have never read so widely and prolifically even during my literature degree. I had no expectations, no requirements, I just read what was available and there for me. No judgement. My final swap was in a hotel on the Khao San Road in Bangkok after winding our way through south east Asia. I ended my journey and flight back to London with another story of travel, another story of wandering in Ireland. The books carried me, were my blanket, my thread, my familiar, my safety in a year of absolute freedom and uncertainty.

There were no books in our house. No, that’s not correct, there were books, but they were locked in the bedroom of the random uncle, and that meant I wasn’t allowed even to see them on their shelves.

The random uncle had been swept up with us when our house in the East End was slum-cleared and we were moved to the red-brick housing estate box. The books he brought with him glittered in my imagination, I knew I wanted to read, the picture books at school were already dead weight. There was treasure behind that bedroom door.

Then the RAF accepted him and he was no longer part of our family. I was the youngest but the complications of gender, relationship and noisy nightmares meant that I was moved into his room. I held my breath as I followed my bedding through that door for the first time, the books were still there! Instantly, in that golden moment, my world expanded 5…. 10…100 times.

There was nothing here that would be considered a childrens book, the uncle was a frustrated traveller, here were foreign lands, strange places, people with different coloured skin. Yet the greatest joy was that there were no librarians to send me back to replace my choice of books on the shelves because they were ‘too old for me’, the ongoing battle I had at the public library.

Nights became adventures, I saved precious pocket-money for torch batteries, I took flight from that unheated bedroom, landing softly (don’t let parents know I’m not asleep) in Africa, Canada, Australia. In the morning I went richer to school, knowing my teachers for what they were, they wanted to ground me in Sunderland. I tolerated their leaden feet, come nightfall, I could journey once more.