The Cure For Sleep: Bedtime Stories

Season 1, 001: where we learn first about the world & its workings

The Cure For Sleep is a memoir about the ways in which we shrink from possibility, and how it feels – and what it takes – to step out of the confines we have made for ourselves.

This month’s extract considers the first stories we are told. After reading, do share a short true tale of your own - no more than 300 words – on this theme in the comments section.

You can read the stories already contributed by readers over on The Cure For Sleep website

march extract

WHERE DOES IT BEGIN, the turn away from risk and adventure that so many of us make? That has us cleave to ease, routine, disguise, conformity? If the events which wake us are often shocking and singular, what leads to a sleep of soul and possibility is harder to trace. We have to go back through all the stories told to us (or by us) about the world and its workings: that bramble thicket in which we lost our will, our way.

I came to consciousness fiercely awake: destructively so, Mother told me – my refusal to go quiet at night (unless laid naked on her chest) being a reason my father left us for another woman in the town below.

How it was to be she and me alone in a last detached bungalow of a tiny settlement on a lampless lane that faced onto an unheeding horizon of field after distant field: frigid, frightening. A time of high alert in which I began to understand not only my own rickety position, but what poor fortune it was to have been born a girl at all.

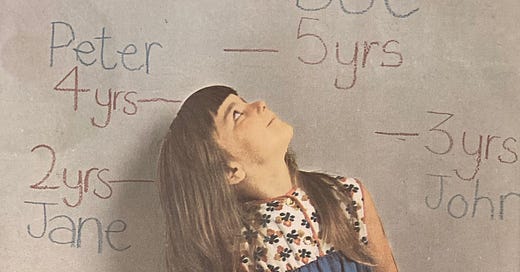

Without a television, and only able to afford a little electricity, we’d watch the kitchen window at dusk and go up the cold hallway together before darkness came, bolting the hollow bedroom door behind us. In winter, when it was often too early for either of us to be ready for rest, Mother drank strong cough mixture to make her drowsy while I – aged two, three, four, five, six – kept guard, rigid and wakeful beside her. The black of country night pricked white in my eyes and noise from the fields pressing in on us had my blood thud with worry: the cough of a cow was always a man outside the thin windowpane; a fox making its nightly rounds was a burglar trying latches. (Too scared to open the door again until daylight, we took a bucket with us in case we needed to pee before morning.)

I had a way of playing with Mother’s heavy black hair that soothed her, and this was my job each evening: To take a small soft strand between my fingers and stroke it to a precise rhythm – picking it up, letting it fall –while she went on til sleep with the only tale it interested her to tell, and me to hear. What There Had Been That Was Lost: A thousand and one stories that taught me the tangled roots of grown ups, and mine in particular.

Once upon a time there was my mother and her mother and hers before that. Née, née, née. Which meant their born name, got from the man that was their father whether he lived or died or stayed or went. But it was still something to know those girlhood names, before they married in to another family, so I should learn them by heart.

Nor should I forget that whatever they wanted was not, in the end, possible.

Mother’s mother’s mother was glad to marry a local hedge-cutter after being sent away when young as a servant in a distant city. She was ready on return for the hard work of farming and child-rearing, but hadn’t expected marriage to make her the carer til death for her husband’s three spinster sisters: One blind, one crooked, and a beautiful third who must be watched always so she wouldn’t die for love of a married farmer (she slipped the latch one day and drowned herself; the ruby brooch in the jewellery box was hers, and would be mine one day because I resembled her so). When the last of these strange charges finally passed away – long after their brother, her husband – Little Granny was free to wish for what she wanted: For Jesus to take her in the night so she could be with her youngest daughter who’d died at three of pneumonia. To this end, she put out her best burial clothes every night and hoped to be gone by the morning. (A small black-papered box was entrusted to us before she went: the relics of her little girl who lived for just a few years in the early 1900s – knitted mittens, a gone-brittle ribbon, horribly soft locks of butter-coloured hair kept wrapped in waxed paper. This, too, it was my duty to learn).

Mother’s mother wanted to be a nurse, but there was no money for training so she was a cook in the Squire’s house until an ill-matched marriage and six children. Her only ambition then was that her own offspring should never have to dip their knee, going instead into respectable work which kept their hands clean: the bank, the police force, the Post Office. Her children adored her as a mild-eyed martyr, who suffered their father and cooked for them all, but even as a pre-school child I resisted her dense gravitational field. I sensed, in a small animal’s instinctive way, how her little sighs and wrung hands had her family choose or stay in jobs that were against their nature. (She kept a jar of her gallstones on display and I understood, too, that this signified bitterness.)

As a young child, I wished to be a borrower; a tiny, sentinel-like, brave presence that would pilfer small objects from our family and feast like a Queen on a single gold-wrapped chocolate caramel. I wanted to live with my parents but for them not to know I was still there; I felt that - at full child size - I was often a burden to them, rather than a source of interest and joy. If I were small, I could live cosily in the airing cupboard where I kept my flower press. I could keep a close eye on the big wide world and alert a grown up to trouble, if needs be. I had a route planned out through the house to the kitchen, with a mechanism of pulleys to snaffle food; a path through the rockery in the garden that would make for perfect borrower-sized adventures; a spot next to the robin hole (a hole in the hedge where our resident robin would nip in and out through the day) where I would set up a camp, complete with tiny campfire, where I would lie on my back and watch the stars come out. When I later learned of the hearth faeries - the broonies and ùruisgs of Scotland - I felt instantly drawn to them, as if a fragment of my soul were some kind of hearth spirit, a tiny protector of home and heart.

Lasting Impressions

Steve Harrison.

It was a ritual that fired up my young, impressionable imagination. Five maternal aunties; a conspiracy of cardplayers were about to plunge into another table top drama. A memory etched in my mind.

Pennies, half pennies, thruppences and tanners were smashed down in the middle of the kitchen table so hard the Babysham bottles clinked and clanked, ringing out the start of the game. Voices cracked the air with expectation. I sucked hard on my sherbet lemon and focused on the players.

White sticks were passed round and set on fire, smoke blown across the table which grew into cumulus congestus cloud enveloping the entire table. I gazed across at them through a smoky haze; mystical figures, faces contorted with frowns, smirks and knowing nods. The local cigarette factory did well on Thursday nights. ( Pay day )

A second sherbet lemon was needed for the next part as cards sliced through the murky air like flying cleavers as shouts of ' bust!' 'twist!' 'deuce!' 'flush!' and 'diamond takes all!' punctured holes through the mist. Glasses were drained, voices clashed, air crackled as cheeks reddened. Cards were slammed down in frustration. Howls and curses marched around the room giving orders.

To a chorus of, ' I'm out! bugger!' Chairs were unceremoniously pushed back and toppled over and fingers jabbed into the air like red hot pokers. The winnings provocatively scraped into an eager pocket. The plunder would eventually end up back in the cigarette factory where my aunties earned it the week before.

Through the smoky haze, my crimson lipped aunties, shining like beacons of hope shuffled the cards to a shout of ' Your deal!' This was unforgettable theatre. They have all now been swallowed up by history, but wait for me in my dreamscapes.