The Cure for Sleep: Gestures, Remembered

Season 2, 009: share a story of a gone loved one - their particular gestures or habits; what those meant to you...

I set myself many tasks in writing The Cure for Sleep, and one of these was to use the memoir form - the story of myself - as a way to celebrate as many others lives as possible: ancestors, family, neighbours, other mothers with whom I shared the early child-rearing days, patients I scribed for at the hospice. To give many vivid glimpses of people who never had or never would write themselves. In so doing, I found myself thinking deeply of gestures: habits, skills or ways of being that were particular to them, and moving to me.

It’s a beautiful feeling, to spend time trying to find a form of words that can convey - in mere sentences - something as large as one’s love, respect or longing for another. I will never forget how it deepened my days, to spend two years on the three drafts of the book that so many of you have now spent time with - and which has been read too by some of the people I’ve described: my first teacher, my husband, my closest female friend, my mentor, his wife.

But it’s also a real challenge to one’s craft: to bring old gestures alive on the page; to balance clear descriptive language with the strong emotions that need to be evoked. One of the passages I found hardest to write was the one in which, at one level, I’m simply lighting a fire…

…and yet I’m making it in the home of a person I love and am losing. And while doing so, I’m remembering how Granny Shadrick (my other great gone love) used to lay a fire in her grate daily. I also needed the passage to show, in concentrated form, something of both my and my Other Love’s deep pasts - all the decades and family traditions we hadn’t shared with one another, meeting in later midlife as we had:

Alone there one cold day, I knelt to the old stove that was hard to keep going. Trying to tend it as Granny had her fire, always fond, slightly girlish, as if wooing it.

That same patient way she and other country folk would hold out handfuls of hay to an animal, or crusts for a garden bird, hoping for it to come; enjoying the slow and uncertain kindling of interest: how it was to care for that man who was finding it hard to decide his life.I felt in the scuttle for the smallest bits of coat to sprinkle onto the sticks I’d lit, taking care not to overwhelm the wood that was still catching. Why could I not find the same restraint and pace with him?…Yes I must learn to hold back instead of always being this fool rushing in.

Putting my hands to my nose, I snuffed at the smoke on my fingertips. Smiled at what we’d been talking about over the phone earlier. Coal tar. What was it really? Why was it used to clean and cure? We’d been swapping memories of our childhood sick days, from being so ill always that autumn (as if even our immune systems were reluctant for us to become close). The bread poultices my mother made me wrap around bad throats; how his gave him crushed aspirin in a spoonful of malt extract.

Oh how old we both were. What I understood, all of a sudden, eyes stinging. Smoke. Longing. Loss. More past time spent apart than we could have as shared future.

Shadrick, Tanya. The Cure for Sleep (pp 250-251). Orion.

your invitation to write

In this holiday season, I invite you to spend quiet time likewise thinking about and paying tribute to a gone loved one at this same close level.

Share a story of their particular gestures or habits; what those meant to you. Have you found a way to keep them alive in your own seasonal rituals or daily ways of being?

[Please read the guidelines for contributors if this is your first submission to the project.]

further reading

This communal project I’ve created around The Cure For Sleep has - as you know - a commitment to strange true tales at its heart.

In that spirit - and in keeping with this month’s theme of gestures - I share a link to a piece written twenty years ago this very day for The Guardian’s Christmas Story slot: its author being another person whose life and gestures I included in my book.

He appears, briefly, midway in my story when I have finally achieved some late and local recognition as an artist, by creating a mile of writing by my town’s outdoor pool. At the point where I invoke his memory, I’m thinking of how it might be time to take no further risks to my reputation…

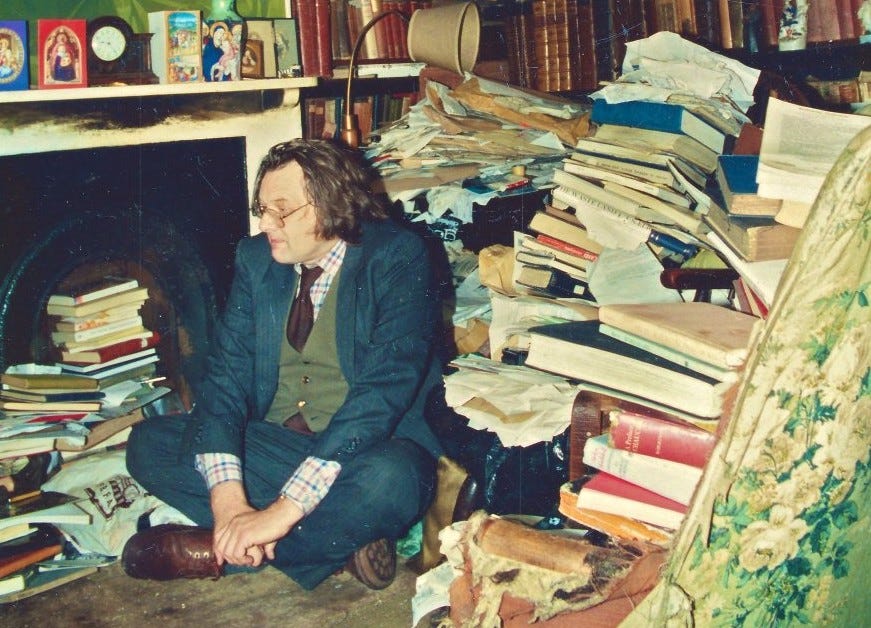

Better now, perhaps, to fade after this second and last summer into one of the town’s eccentrics who were spoken of with fondness not alarm. Like the gone-now university lecturer who went always along the same badger tracks for his daily walk - head full of Eliot and the Bible.

That man was Stephen Medcalf - and once upon a time he had a student called Ian McEwan: who many years later, and by then a renowned author, urged his old tutor to write for The Guardian.

A Light in the Darkness is the result: the story of a startling discovery this lifelong bachelor and man of habit made as he was walking home through our small Sussex town one night…

You can read more about Stephen Medcalf and his house on New Road in Lewes (street of my own first adult home, as described in The Cure for Sleep) at the Bible of British Taste.

My great-uncle Carleton always greeted us with a handshake, even when I was very young. I am certain he was the very first person to shake my hand, taking it upon himself to teach us children the proper technique, to say “How do you do” and to ensure the correct pressure, gently correcting us if our grip were too tentative or too powerful. Carleton always expected this formal gesture, a handshake delivered with just the right balance of confidence and respect. He also was likely the first to call me “Miss”, another dose of formality that was foreign to my world but essential to his.

I don’t ever remember seeing Carleton without suit and tie and hat, but I do remember seeing him sitting in our den with a handkerchief on his bald pate. He had gotten chilly and had taken out his starched white gentleman’s handkerchief, tied a knot carefully in each of the four corners, and then placed it upon his head as if that was the most ordinary and proper thing for a chilly gentleman to do.

I was never entirely sure how seriously he took his proper gentleman-self. There was always a glint in his eye that suggested humor, a warm affection in his way with children, even while calling us “Master” or “Miss” and insisting on just the right handshake. Years later, when anyone reaches a hand out to me, my arm becomes a conduit for carrying on Carleton’s education, and somewhere inside me, formality and amusement waltz together.

Gestures, Remembered

by Susan Bennett www.shedwriting.com @shed_writing

One evening, I surprised myself by reaching into the cupboard and picking a bottle off the highest shelf. HP Sauce. Brown and spicy and now in a plastic bottle, rather than the glass one we used as kids. That thump thump on the end, trying to get some brown sauce to plop pleasingly on our plates, beside the sausages and bacon and soda bread. And the inevitable shout of frustration when nothing came for ages and then a massive slop. Ah, it’s all over my soda bread! It makes it all soggy!

Maybe plastic is better these days, I think, as I squeeze out a perfectly sized drop on the edge of my plate. It’s an Ulster Fry (of course) and it never tastes right without HP Sauce. This was a surprise tonight, though. I’ve told myself, over and over again, that I don’t actually like this sauce with a fry; I prefer some fancy chutney, I say with a middle-class sniff.

But here I am, dipping the sausage and enjoying the taste immensely. My brother was right. Stephen slathered the stuff on every single meal (except breakfast, but I wonder if, given the chance, his cornflakes would also swirl around in brown milk). As kids, we would pass the bottle round, watch intently as each person tried to control the amount coming out, and laugh and laugh when it went everywhere. I didn’t know that my big brother, with his freckles and wonky fringe and odd tastes, was wise and funny too. He was just annoying. And then illness arrived and, too late, pointed it all out: he was wise and funny.

And so here I am, missing him and licking the brown sauce that tastes now of spice and warmth and tears.

Here I am. Missing him.