The Cure for Sleep: Why Do You Write &...

Season 3, 006: …what challenges do you face when doing so?

Welcome to Issue 6 in Season Three of The Cure for Sleep on Substack: this companion project to my memoir of waking up, breaking free and making a more creative life. It’s a place where you can explore your own most important memories and motivations in the company of others who are also interested in the art of life-writing and self-examination.

Why do you write? And what are the biggest challenges you face when doing so?

I turn fifty at the end of October, and as a birthday offering to you all, I’m asking you to reflect on this question (with a word limit of 500 words rather than usual 300).

When I first sent this post, I said I would be selecting one contributor for a free mentoring session: that writer was

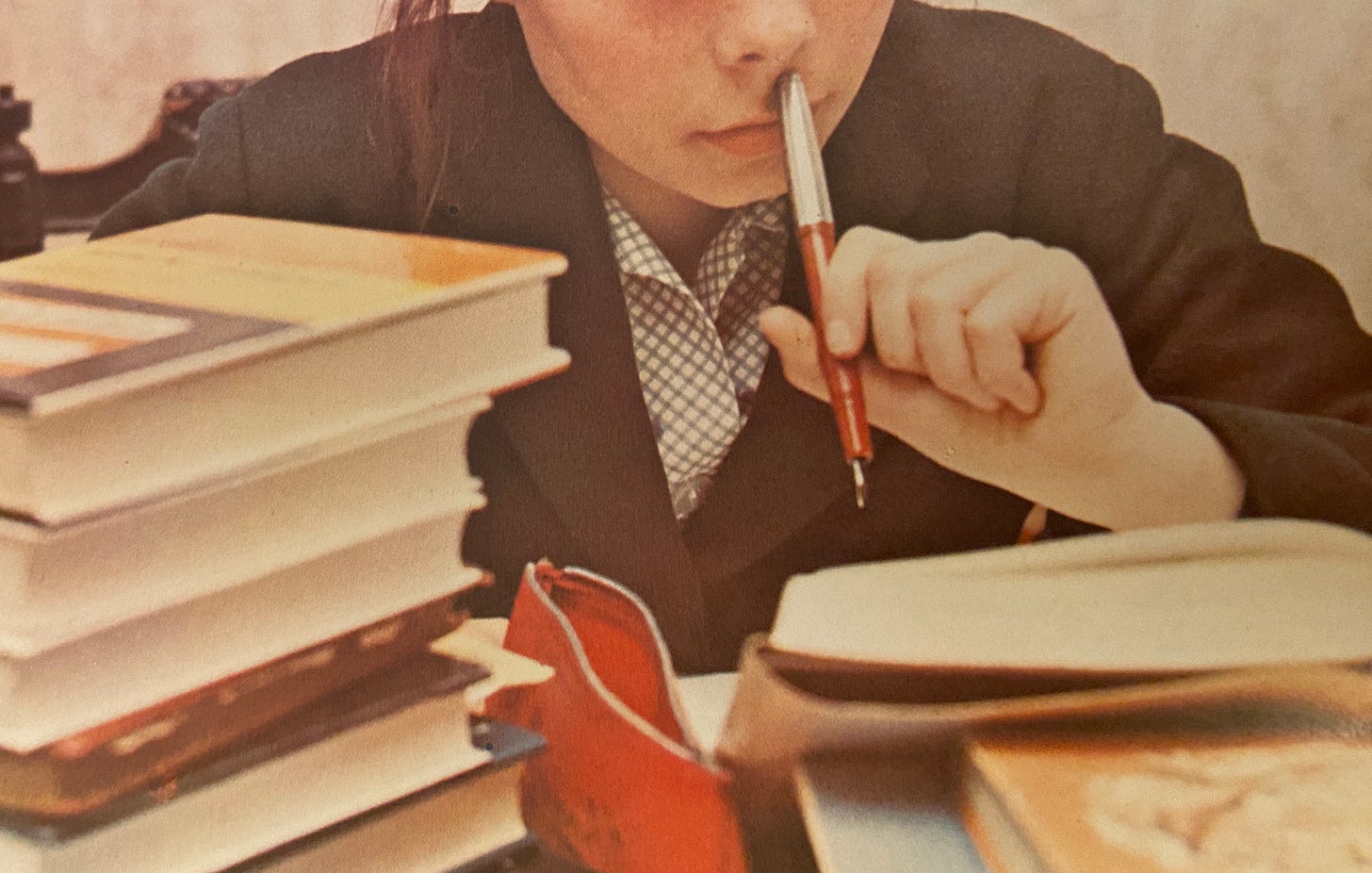

- a hospital doctor and mother of a young child. We shared a long zoom call in early 2024, and it has been a pleasure to follow her creative developments over on her own Substack Hospital and Home since then. Scroll to the bottom of this post to read Zofia’s piece.If you’ve read The Cure for Sleep then you know that it is - at heart - a story about becoming a writer, an artist. What it took for me to own that lifelong desire and make it material, when I come from a place and people where the use of pen and paper was confined to school and business. So that, even with an agent asking for the story of my life, I was still having to do battle with myself at a desk to believe I could do it (even with a public mile of writing, paid residencies, and many small published pieces behind me):

I look now at the hand holding the match and I circle it this way, that. Still there, and working. In the night it was taken off clean at the wrist, so that I carried it about in my left one, help- less. This repeating motif through my whole childhood made urgent, and appalling, through dream code: how my father as a young man, disinherited from the family farm, was told he had his hands and could be a mechanic; how I, clever, in the next generation was taught by Mother and my teachers that I wouldn’t need mine.

Knowing then that here it was, the great decisive moment of my life. Concluding, in sleep, that writing – the expression of belief – is, after all, a manual labour no less than the care of farm animals and small children. And need not be the severance from family and class I always feared. Or if it is, then I’m ready now to bear those losses.

/…/

Who am I then, and where, this woman awake in her only and third life who is writing a book at last, after reading so many for so long?

Here, in this wooden room on wheels, it the end of January in a year when my small country begins its retreat from Europe. In the silence I feel the hut and my tiny island drift away from the protections and constraints of being joined with those other countries.

How shrunken life has begun to feel: resources and freedoms being daily stripped away. It is so easy to feel inert and without purpose. What use any one small soul?

But then a phrase from my time as a hospice scribe returns to me: It’s not much, but neither is it nothing. And so I will try and write a book of my own, inch by inch, that might reach beyond my narrow self and add to the ration of courage that stories are for us all.

During the long years of my self-made apprenticeship, I spent many hours studying the journeys to publication of authors I admired, in order to become a person who could make her own public statement of purpose. Of all the many stories I collected during that time to create momentum and self-belief, the ones I still find the most exhilarating are Turkish writer Orhan Pamuk’s responses when made a Nobel Laureate of Literature in 2006. His shorter one for the Banquet speech is as follows:

Why do you write? This is the question I’ve been asked most often in my writing career. Most of the time they mean this: What is the point, why do you give your time to this strange and impossible activity? Why do you write … You have to give an excuse, an apology for writing … This is how I have felt every time I’ve heard this question. But every time I give a different answer … Sometimes I say: I do not know why I write, but it definitely makes me feel good. I hope you feel the same when you read me! Sometimes I say that I am angry, and that is why I write. Most of the time the urge is to be alone in a room, so that is why I write. In my childhood I wanted to be a painter. I painted every day. I still have that childish feeling of joy and happiness whenever I write. I write to pursue that old childish happiness and that is why for me literature and writing are inextricably linked with happiness, or the lack of it … unhappiness. In my childhood, I felt happy, painted a lot, and all the grown ups were constantly smiling at me. Everybody was gentle, polite and tender. I wrote all about this in my autobiographical book, Istanbul. After the publication of Istanbul, some people asked me this question: Aren’t you a bit young to write your autobiography? I kept my silence. Literature is about happiness, I wanted to say, about preserving your childishness all your life, keeping the child in you alive … Now, some years later, I’ve received this great prize. This time the same people begin asking another question: Aren’t you a bit young to get the Nobel Prize? Actually the question I’ve heard most often since the news of this prize reached me is: How does it feel to get the Nobel Prize? I say, oh! It feels good. All the grown ups are constantly smiling at me. Suddenly everybody is again gentle, polite and tender. In fact, I almost feel like a prince. I feel like a child. Then for a moment, I realize why sometimes I have felt so angry. This prize, which brought back to me the tender smiles of my childhood and the kindness of the strangers, should have been given to me not at this age (54) which some think is too young, but much much earlier, even earlier than my childhood, perhaps two weeks after I was born, so that I could have enjoyed the princely feeling of being a child all my life. In fact now … come to think of it … That is why I write and why I will continue to write.

His Nobel Lecture - ‘My Father’s Suitcase’ - develops this theme in more depth, to moving effect. And begins so…

Two years before his death, my father gave me a small suitcase filled with his writings, manuscripts and notebooks. Assuming his usual joking, mocking air, he told me he wanted me to read them after he was gone, by which he meant after he died.

‘Just take a look,’ he said, looking slightly embarrassed. ‘See if there’s anything inside that you can use. Maybe after I’m gone you can make a selection and publish it.’

We were in my study, surrounded by books. My father was searching for a place to set down the suitcase, wandering back and forth like a man who wished to rid himself of a painful burden. In the end, he deposited it quietly in an unobtrusive corner. It was a shaming moment that neither of us ever forgot, but once it had passed and we had gone back into our usual roles, taking life lightly, our joking, mocking personas took over and we relaxed. We talked as we always did, about the trivial things of everyday life, and Turkey’s neverending political troubles, and my father’s mostly failed business ventures, without feeling too much sorrow.

I remember that after my father left, I spent several days walking back and forth past the suitcase without once touching it. I was already familiar with this small, black, leather suitcase, and its lock, and its rounded corners. My father would take it with him on short trips and sometimes use it to carry documents to work. I remembered that when I was a child, and my father came home from a trip, I would open this little suitcase and rummage through his things, savouring the scent of cologne and foreign countries. This suitcase was a familiar friend, a powerful reminder of my childhood, my past, but now I couldn’t even touch it. Why? No doubt it was because of the mysterious weight of its contents.

I am now going to speak of this weight’s meaning. It is what a person creates when he shuts himself up in a room, sits down at a table, and retires to a corner to express his thoughts – that is, the meaning of literature.

It was moving, unbearably so, to find myself in a similar situation this summer: on the first day that I arrived to nurse my mother for the final time, she asked me to reach into the back of her wardrobe - ‘there’s a suitcase of my diaries I want you to have.’ They are upstairs now, unread months later. Perhaps I will spend my fiftieth birthday - my first without her - daring to read her words, and allowing myself to feel fully all in her life that never called forth a response from others. Whereas I share that joy which Pamuk describes, despite the great difference in my reach and reputation. Like him (and unlike his father, my mother) from my small room in which I spend long, unseen hours, I’ve found a way to share my stories with others, and to hear stories in return…

Which is why this feels like the most soulful prompt to set in the days before my birthday month begins.

how to take part

For this prompt only, you have 500 words instead of 300. Use the comments field below this post on Substack to submit your words.

[Please read the guidelines for contributors if this is your first submission to the project.]

The Story Begins

by Zofia K Stanley

The story begins a long time ago. Long before you and I were born. Long before our parents met. Long before our grandparents grew old.

The story begins generations ago. In a land and time long gone. In languages and cultures that have changed beyond recognition. Inside of me it lives on.

The story begins a long time ago. But it continues to unfurl day in day out, its threads run through the tapestry of day-to-day existence: a bold crimson here, an ugly grey there, a faltering gold, a steadfast green, here are the threads that make up who I am, the threads that can be traced back across the years through the people the lands and times that made me who I am, and every day the story grows, a soft and steady amorphous mass, this is who I am who I am who I am.

Why do I write? Because when I write I take up the mantle and make it mine, when I write I grasp these cloths and bring them close, the dim and dark, the silvery light, I take them up and draw them in, the tangled threads, the knotted yarn, I take them up and draw them close, this stuff of story, this story of mine. I dissect, I embroider, I shape.

I must write. I feel the draw so keen so clear, the tug at my heart the voice in my ear, you must you must you must you must. I muster up the will to try, I sit, I start, I falter. I must I must I must I must – do more. Before I sit before I start I must do this I must do that, an endless list a bottomless vat, I must do this I must do that.

My life: a mother, a doctor, a daughter, a wife. Fulfilling, so full, exhausting, time-poor. I simply don’t know how to create space for more. My baby cries, my body aches, chores pile up, anxieties aggregate. My world grows small. But the story goes on and on and on, the story calls, it wants to be told. I want to tell it before I grow old.

about tanya

author site | book site | instagram

I write because what if as I began to piece together the first white gossamer shreds of memory, they are ripped away, leaving nothing of my beginnings by blackness, a slight limp and a distinctive laugh?

I have no memory of my original mothers voice, but there were times growing up when a familiar intonation, a wind blown conversation brought on a sharp intake of breath, and an almost unstoppable need to find its origin. I was caught between the desire to follow the voice and the dark shadow of abandonment. It set the rhythm of my days and it took a lifetime to change it.

For the first 40 years of my life, my bloodline was unknown to me, grafted onto a branch of English archbishops, genealogists, itinerant Norwegian weavers , professors, inventors, explorers, restless men, and unhappy women.

But the music of my beginnings would not let me be. It hummed through open windows, piped up through my bare feet and plucked my untamed hair. It came in the drone of the dulcimers strings in the songs of Ann Grimes, an early collector of Appalachia, music, and mother of my best friend, Sally. It came out in a cadence of a Carney man’s call, in the fire lit stories the tramps and travelers told stopping by the Olentangy River on their seasonal journey from southern mountains. It arrived in the bales of freshly shorn sheep‘s fleeces, in the whirl of the spinning wheel, and the sissing sound the threads made as they slipped through the hand set a reeds of a 100 year old loom. All these things were carefully piled at the edge of memory. They so changed the hue of the blackness that abandonment lost its power.

I stepped beyond the carefully laid out prison walls of my beginning to start the journey.

My earliest memories revolved around a black emptiness from whose edges blew a dry, cold ice like mist. When I was older and could use the dictionary, I was able to name this place which lies back of the beyond.

It was oblivion, the state of being forgotten.

My challenges are time, beginnings and endings….

Will I, at 82 be able to put all I found, in readable form.

.

Purge the panic and surge with joy

I write because I need to be consumed and subsumed by something bigger than my entity. I want to mend the severance of my grief and bridge a chasm of desolation with curiosity and exploration. I want to reach through the shrouds of loneliness and beyond the masks of coping to empathy for others. I write because I have no other God to call upon for safety, succour, or salvation.

Every morning I wake up to lumpy thoughts swirling into syllables which then mould themselves as words. When I write, I face my irascible monsters and turn them into pets. I listen to them, stroke them and encircle them with love as they doze by my side. I am grateful for my fears, grief, loss and loneliness because each facet plays it’s part to rebuild, renew, restore me. Writing helps me to pause my judgements and cultivate compassion, not just for other people, but also for my past, present and future self. Through writing, I have learned to tell my truth in a way that I’ve never had the courage to reveal verbally. I think of the process as a loving labour like revealing a rough gemstone’s glory by cutting, polishing, setting and wearing.

I’m challenged by ineptitude, self-doubts and a total absence of hope to write one single word of worth. Writing questions my validity, yet words ratify my existence. There are days when I am overwhelmed by doubt and paralysed by fear, preventing me from writing. I ask myself “Why is this hard and what am I scared of?” Then, I capture all codswallop tumbling from my mind and give my brain free reign and rein to splurge it’s jumbled pain. Just like the contents of a drawer tipped upon the floor, each thought is gathered, studied and recorded. Emotions are woven into words to create a cord to form a chord for a reader.

The next phase is taking my piece to my writing group for feedback. When joining such a group was first suggested I reacted with a severe panic attack. Within an hour of internet research I’d found a group online and had approached the organiser for joining details. It’s the only way I know to overcome my anxieties. Within twenty-four hours I was sitting in front of my computer listening to incredible people reading their work and listening to feedback. It took me a month before I set myself the goal of presenting a piece to the group. Now, I look forward to people telling me what they need more of and where they think I can improve. I relish the exposure a lazy or cliched sentence and immediately get excited about how I can re-write, improve and think deeper about what I really want to convey and how best to deliver. Despite my craving for connection, I’m filled with awe when others express that I have touched them.

Shazz Jamieson-Evans